A secret ring of poisoners killed 600 men in 17th century Italy––and they nearly got away with it.

Thou shalt not kill. The commandment, etched into stone, did not stop hundreds of women from killing their husbands with the help of Giulia Tofana, the most notorious poisoner in history.

A few drops of her special potion, aqua tofana, could kill a man in a matter of days.

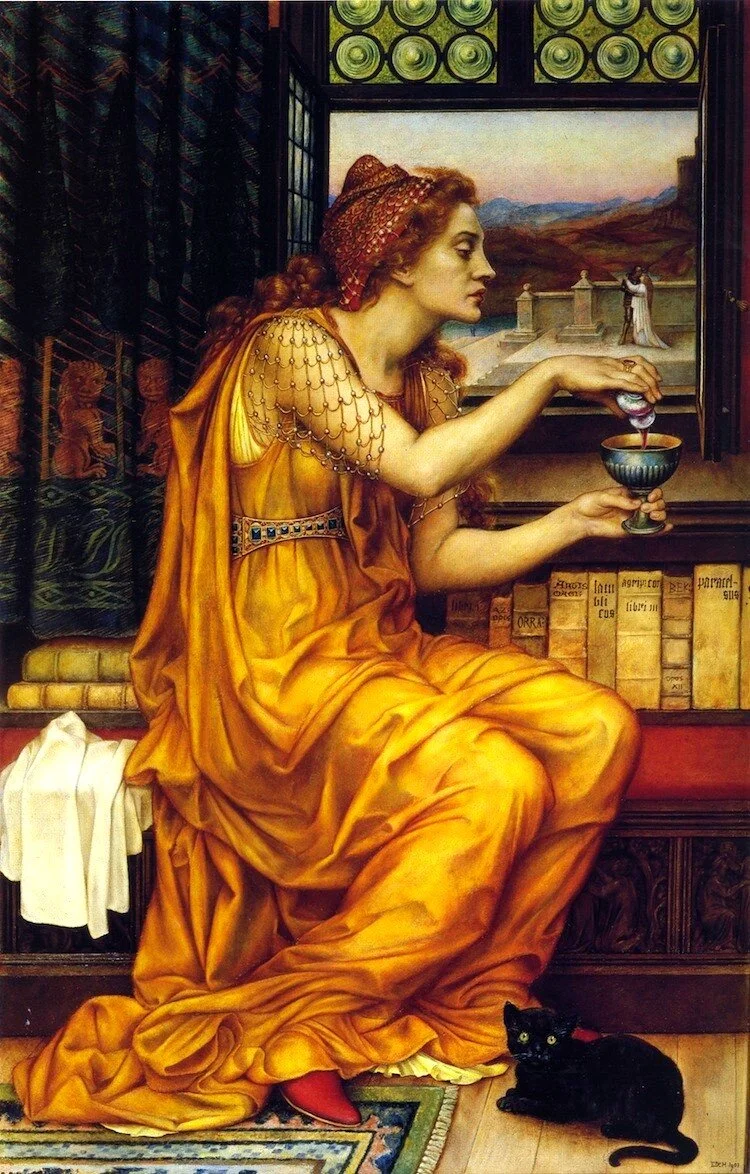

Evelyn de Morgan, The Love Potion, 1903

But these weren’t your typical mass murderers. The poisoners were female apothecaries who offered a particular potion to women trapped in unhappy marriages. Led by Giulia Tofana, they mixed a deadly concoction that killed slowly, releasing women from the bonds of matrimony by killing their husbands.

To Tofana and her customers, death was a necessary evil to free women.

Who was Giulia Tofana? And why did she sell the deadly drops that could kill a man in a matter of days?

Aqua tofana contained a deadly blend of ingredients. Arsenic, found in many women's cosmetics in the 17th century, could kill in a high enough dose. So could lead. The final ingredient, belladonna, was also used in small doses as a makeup. Women would take the juice from the nightshade's berries and use it as eye drops to dilate their eyes.

Illustration of Belladonna

It wasn't difficult, then, for Giulia Tofana and her apprentices to simply mix a stronger dose of these poisons and market it as a healing oil or cosmetic.

And aqua tofana was odorless, colorless, and undetectable in the 17th century––making it the perfect poison.

When women bought the potion, it came with detailed instructions.

Wives carefully hid the poison among their cosmetics and oils, where it blended in thanks to the vial marked with the name of a fake healing oil. Then, they should add a few drops to their husband's wine or food. One dose didn't kill. Instead, it weakened the victim.

A second dose, administered a few days later, would cause stomach cramps and vomiting. Instead of suspecting poison, victims assumed they had a natural disease. After a third dose, most victims died.

The slow method of poisoning had several advantages. Victims had days to repent their sins and prepare for death. For Tofana and her customers, this was key. If their victims repented and saved their souls, it lessened the crime of murder.

And wives often had very good reasons to poison their husbands. In 17th-century Italy, divorce was impossible for married women. Wives had few legal rights––their husbands controlled their finances, their dowries, and even their movement. Many wives spent their days locked away in their homes, only allowed outside with a chaperone.

Abused wives could not take their husbands to court.

The courts often prioritized marriage over everything else. Consider the case of Artemisia Gentileschi, a Roman teenager raped by one of her father's colleagues in the 1610s. Artemisia took her rapist to court––and the court suggested the pair marry. Women were often encouraged to marry their rapists as a way to preserve their honor––regardless of whether the women wanted to be shackled for life to their rapists.

Artemisia won her case and did not marry her rapist. But since he was friends with the pope, her rapist got off without any consequences. The trial destroyed Artemisia's reputation in Rome and she was forced to leave the city. Fortunately, she made a name for herself as an artist, becoming the first woman in history to support herself with her art.

Artemisia's favorite subject was women murdering their male attackers. She painted multiple versions of the Biblical tale of Judith, who beheaded an enemy general named Holofernes. On her canvases, Artemisia took her revenge against her rapist.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes

Other women had fewer options. A woman married off to her rapist might turn to Giulia Tofana for a remedy.

Around the same time, Beatrice Cenci, another Roman teenager, went to her death for killing her abuser. Beatrice was the daughter of a Roman nobleman named Count Francesco Cenci. Her father repeatedly raped her and beat her siblings. When Beatrice went to the authorities, begging for help, the count escaped punishment because of his title.

Beatrice and her siblings plotted to kill their father. In 1598, Beatrice, her siblings, and their stepmother beat Count Francesco in the head with a hammer and tossed his body over the balcony of their castle.

They tried to make the death look like an accident. But police instantly suspected the family and placed them under arrest. The siblings endured torture in a Roman prison before a court convicted them of patricide.

Fearful that other children would murder their fathers, Rome's most powerful person, the pope, pushed for an execution. On the morning of Sept. 11, 1599, Beatrice Cenci marched through the streets of Rome and climbed the steps of the scaffold to lay her head down on a block. An executioner beheaded her with an axe.

Beatrice and her siblings might have gotten away with murdering their incestuous father if they'd turned to aqua tofana instead of throwing him off a balcony.

Giudo Reni, Portrait of Beatrice Cenci

Italy's most famous female poisoner, Lucrezia Borgia, also used her potions against unwanted husbands. Married off several times by her father Rodrigo Borgia, also known as Pope Alexander VI, Lucrezia reportedly killed at least one of her unwanted spouses.

When women had no control over their lives and no legal remedy for abuse, they turned to people like Giulia Tofana.

Bartolomeo Veneto, Portrait of a Woman (possibly Lucrezia Borgia)

Was Giulia Tofana a serial killer? She likely didn't think of herself in those terms. No, to Tofana she simply provided a service. Her customers decided whether to use her potions or not.

But the authorities didn't see it that way. Giulia Tofana also lost her life––thanks to a client who got cold feet.

In 1650, a bowl of soup landed Giulia Tofana on the chopping block. One of Tofana's clients dosed her husband's soup with aqua tofana. But she cried out as he raised a spoonful to his mouth. The suspicious husband turned on his wife, abusing her until she confessed that she'd poisoned the food.

The woman eventually pointed the finger at Giulia Tofana after Roman authorities tortured her.

Tofana tried to escape. She sought sanctuary in a church––yet rumors swirled that the poisoner had turned her skills against the entire city, dropping her concoctions into the public water supply. Tofana and her apprentices were executed in Rome.

Was Giulia Tofana a hero or a villain? Her story does not fall easily into either category. Tofana sold poisons––and she confessed that her clients killed over 600 men. Yet she almost certainly saved lives as well. While Tofana's solution crossed moral lines, the need for her services condemns her society. With no options, women turned to poison to protect themselves.

The true story of Giulia Tofana inspired my most recent series, the Belladonna's Kiss Trilogy. The trilogy, set in the time of Lucrezia Borgia, imagines an elite group of women trained to poison abusive men. They take their name––Belladonna––from the poisonous plant that kills their victims.

Giulia Tofana was not the only poisoner freeing women from abusive husbands in early modern Europe––with few methods to detect poison and a market for deadly concoctions, others must have plied a similar trade. But unilke Tofana, they were never caught. That notion gave birth to the Belladonna and the world of the Belladonna’s Kiss Trilogy.